Tethers to the Soil: A Valley’s Cultural Afterlife

By

Arsch Sharma

It is Christmas, 2021, and my eyes rest on these whitewashed walls of a Hauz Khas cafe. It’s almost as if summer lives in this space, in this house with salt upon its walls. Entangled in the fantastic cat’s cradle of taillights out the window, I am somehow humbled into a bleeding familiarity: one flowing out of yarn that wraps around the fingertips, one that flows into wooden looms that sit clacking in village verandas back home.

It is a winter far removed from my winter: one coloured blue in poplar and elm smoke from the tandoor, air stiff with a conversation: words coming and going in waves: lore and common gossip indistinguishable from one another. Women spinning yarn from balls of fleece, their wooden spindles whirring upon the cedar floor like ancient totems; and in the short-lived spells of silence when suddenly everyone seemed to run out of words, the spindles would continue to warm the air. Strings, in all forms: made of wool or made of red taillights, possess an immense power to tether. And perhaps they assume a greater significance in the bleak winter when the earth is asleep and spirits are wild.

I remember learning how to spin yarn from a grandmother of mine: how she told the eight-year-old me that there were different spindles for different kinds of wool - the tiny ones for spinning pashmina and fine fibres, and the bigger ones for coarser wool. It’s a tricky business, to get a hang of how the yarn flows out of the fleece: one must learn to ease and regulate it to achieve the desired thickness. She taught me all this while holding my tiny hand in her hand, in a way that buried all our differences in love.

I remember learning how to spin yarn from a grandmother of mine: how she told the eight-year-old me that there were different spindles for different kinds of wool - the tiny ones for spinning pashmina and fine fibres, and the bigger ones for coarser wool. It’s a tricky business, to get a hang of how the yarn flows out of the fleece: one must learn to ease and regulate it to achieve the desired thickness. She taught me all this while holding my tiny hand in her hand, in a way that buried all our differences in love.

“You’re lucky”, she would say as the winds raged outside in the dark Paush (the dark and the coldest month, mid-December to mid-January, when evil spirits are most notorious) nights, “To have such soft wool these days. We don’t find desi wool anymore, it is all vilayati (foreign) now.” And her words would summon a sea of low groans of agreement from everyone around. “It’s even softer than the wool from Lahaul, our sheep have all gone extinct.” Perhaps even wool goes extinct because I haven’t come across blankets as coarse and itchy as the ones she used to wrap me in. It wasn’t until the turn of the last century that cotton was adopted by the Kulu valley, and the itchy wool was what made us natives of this land. She told me coarser wool meant a coarser yarn, stronger strings. Years after those evenings, I do not doubt it one bit.

For centuries, families have been hand-spinning yarn in mountain cultures. The bitter winter and cooler temperatures made cotton cultivation impossible in most of the Himalayas save perhaps a few ranges in the foothills. Wool was, and in some places still is, the norm. A trip to our villages even on the hottest day of June wouldn't be devoid of spectacles of older men and women dressed in wool pattus and coats. Most of these garments are hand-spun and hand-woven, but with the advent of industrialisation in the hand loom sector, machines and mechanised mills have replaced human labour.

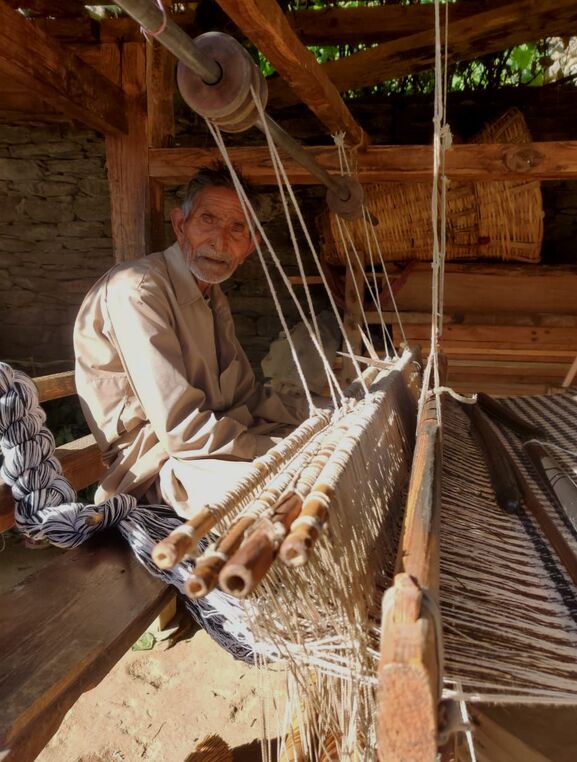

A makeshift rachh used to be part of every household in the villages of Kullu valley, Image Credit: Peter Van Geit

The process of making wooden fabric traditionally is quite simple. It all starts at the wool: other than the almost extinct desi wool (years of breeding with merino sheep has resulted in an overall softer wool fibre even in the average Kulu sheep), Merino wool and Lahauli wool are the most common type of wool that is used for day-to-day garments. “Ladechh oon”, my grandmother would tell me is softer because of the nature of grass that grows beyond the Rohtang (the natural mountain pass between Kulu and Lahaul valleys). The Merino comes from Australia and is now quite popular because it surpasses even the wool from Lahaul in its softness. Pashmina is obtained from areas bordering Tibet, from where some other varieties came too, which included Ibex (called Tangrol in the Kulu dialect, hunted for its meat, wool and horns) and Yak wool. The trade was easier when the land silk route was functional (stories of huge trade fairs at many places, even at Baralacha-la and Sarchu have been a part of my childhood, where novelties and riches from as far as Pamirs, Samarkand and China were traded), and the transactions were mostly barters.

The softer the wool, the more unsuitable it is for the average Kulu native’s work. Working in fields and orchards, and even everyday living in the mountains means some amount of physical labour that can’t be avoided except by the privileged. A rougher fabric is preferred by those who work outdoors since it can withstand the elements and the usual wear and tear.

The wool is often sold locally during and after Dussehra: the reason for this is that gaddi shepherds return from the high altitude meadows around late September or early October when the weather begins turning inclement. This is the time when the best wool and the most prized meats enter the market, the sheep and goats having grazed on the nutritious Niru (a variety of grass that grows in the high altitude meadows only during the short Himalayan summer) grass and wildflowers all through summer.“In the old days”, she tells me, “They would carry grains and ration to the Hamta (a mountain pass near Manali, that connects Kulu and the Spiti valley. Not motorable, this pass was extensively used before cars and metalled roads made alternative routes more convenient), where they would barter it for wool. That’s how we co-existed, it was all communal.”

The softer the wool, the more unsuitable it is for the average Kulu native’s work. Working in fields and orchards, and even everyday living in the mountains means some amount of physical labour that can’t be avoided except by the privileged. A rougher fabric is preferred by those who work outdoors since it can withstand the elements and the usual wear and tear.

The wool is often sold locally during and after Dussehra: the reason for this is that gaddi shepherds return from the high altitude meadows around late September or early October when the weather begins turning inclement. This is the time when the best wool and the most prized meats enter the market, the sheep and goats having grazed on the nutritious Niru (a variety of grass that grows in the high altitude meadows only during the short Himalayan summer) grass and wildflowers all through summer.“In the old days”, she tells me, “They would carry grains and ration to the Hamta (a mountain pass near Manali, that connects Kulu and the Spiti valley. Not motorable, this pass was extensively used before cars and metalled roads made alternative routes more convenient), where they would barter it for wool. That’s how we co-existed, it was all communal.”

The Hamta: I have spent hours looking at it from my window: the mountain where we are all bound to go, for it is also the route that is taken by one’s spirit in the afterlife.

Several people have reported seeing dead people along its ascent, talking and chatting as if they were still alive. “Once”, she went on sipping her tea, laughing, “there was one such barter at Hamta, where a crafty man tried tricking the Lahaulis. He put rocks in their sacks of wool, thinking that he’d pulled a fast one on them. It wasn’t until he got back to the village that he realised he should’ve put them in the grain to get more wool!” Times were simpler back then, I reckon. Trickery is an import, after all.

During long winter evenings, after the cattle are brought indoors, there isn’t much to do. This is when women and men carry their spindles and fleece and gather around the tandoor. Venues are often chosen by turn, but now, the social fabric of the village is fraying bit by bit as people resign to store-bought winter wear and fashionable accessories that symbolise modernisation to the uninitiated mind. It usually takes a month to spin half a kilo of wool: the finer the yarn, the more time consuming the process is. And come spring, the weaving begins with gusto. Even though cooperative societies have made it a mass exercise, one can still find small independent families who sit out in their verandas, working on the rachh (the traditional hand-loom that produces narrow-width fabric as compared to the more recent, larger khaddi hand-loom). The designs are diverse: ranging from magholu (inspired by the shape of hemp hearts, diamond-like patterns), lehriya (herringbone), chitra (checkered, of all sorts and sizes), and several more. Shawls and pattus carry more ornate designs (usually, but not always) than the pattis (heavy wool fabric for coats and overcoats). Patti’s are then subjected to hand-milling: a process that shrinks them and adds to their thickness. This too is a process that is fast disappearing in the light of rapid mechanisation. The town of Mandi still remains the hub of hand-milling, where woven Pattis are soaked and washed and stretched on tenterhooks. Once milled, the fabric is ready to be tailored into garments.

Last winter, I hiked up the slopes of Hamta, and as I ascended along that frozen trail a strange forgetfulness came upon me. The strings that held me seemed to grow frail as I looked at my valley below, threaded by the Beas, lined by houses and villages that had grown too small to see. Perhaps it is something of an afterlife that is upon us, upon the culture of this soil.

|

05/02/2022

|

Explore | Share

|

|

He has been an independent creative writer for almost three years now, and his works encompass creative fiction and creative non-fiction genres. He has penned short stories, articles and poetry that has been published in various magazines and platforms. He published his debut novel, ‘Miasma’ in 2020, which is a work in the existentialist genre.

|